For whom the bell tolls

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were; any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

John Donne, Meditation XVII, 1623

National accountability is needed to scrap the gap between behaviour policy and reality

All new teachers in tough schools have felt that visceral fear in the pit of the stomach when the bell goes for their most disruptive class. But no teacher is an island. Every teacher is a part of the main, and if any teacher, new, supply or otherwise, is confronting a torrent of abuse, or even assault, that diminishes the school. The bell tolls not so much for the new teacher, as for senior leadership.

John Donne, satirist, poet, preacher and dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, lay dying in Lent of 1631. He rose from his deathbed to deliver his last sermon, Death’s Duel. He drew on the parable of the two builders, one of whom built his house on rock, the other on sand; one house stood firm against the storms, the other collapsed in ruin as its shifting foundation got washed away: ‘buildings stand by benefit of their foundations that sustain and support them: the foundations suffer them not to sink.’

Just as durable buildings require firm foundations, schools depend on a sound foundation of firm discipline. No one learns anything in a class where disorder is the norm and the teacher has lost control. Inconsistent school discipline is like building a house on sand and expecting it to stand firm.

Disruptive behaviour is a national problem

Let’s establish first that there is a problem with behaviour nationally. Having taught across many challenging schools, education blogger Andrew Old establishes unequivocally that there is a problem. What he says resonates with many teachers, and his blog gets some 500 views a day:

If children are going to learn then it is absolutely vital that they do what they are told in lessons. If schools are going to be safe and orderly then it is essential that they also do what they are told outside of lessons. If teachers are going to be effective then they cannot be constantly faced with the stress of confrontation, defiance and chaos. The minimum standard required for effective teaching is that all teachers (not just SMT or teachers who have been around for years) can expect students to comply with all of their instructions first time. The minimum standard for teaching to be a desirable profession is that teachers have freedom from fear when it comes to giving instructions and enforcing rules. Too many schools simply do not have those standards, and as a result teaching is very often stressful and unpleasant.

The experience of so many new teachers in tough schools, as their articles attest, is of frustration: ‘Pupils know that their school is chaotic and that most of their misbehaviour will go unpunished’; ‘it’s the children’s education that suffers’. But the evidence for this is not just anecdotal.

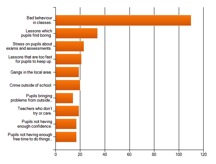

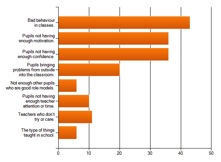

In proprietary research, Policy First, a teacher-led think-tank within Teach First, surveyed almost 500 pupils and nearly 250 teachers in challenging schools. The survey asked what issues made it more difficult for pupils to work towards the life they want when they’re 25 years old. The results showed a striking consensus. Both teachers and pupils ranked bad behaviour as the most important single barrier to achievement. In the survey, 79% of teachers and 53% of pupils selected bad behaviour in classes as an issue. When asked to rank the five most important issues, three times as many pupils ranked bad behaviour as their most significant issue compared to any other (see charts 1 and 2). For teachers, bad behaviour also ranked as more problematic than the next most significant barriers, motivation and confidence. When surveyed by the Department for Education, 60% of teachers felt bad behaviour was driving teachers away from the profession. Attrition rates of 50% of teachers leaving the career within five years of qualifying, and a turnover as high as 50% annually in the most challenging schools, testify to the problem. Disruptive behaviour is by far the biggest barrier nationally to pupils achieving their aspirations.

Chart 1. Pupil ranking of issues by importance

Chart 2. Teacher ranking of issues by importance

Misbehaviour is caused by inconsistency

So why is this happening, and what is to be done? The biggest cause of misbehavior is inconsistency, within-school variation and poor enforcement. If pupils realise they can get away with behaving badly, without facing consequences, they will continue to push the boundaries. It is a rare teacher who can ensure discipline in the classroom without a consistently implemented policy at school level.

A deeper cause is the damaging preconception that discipline is a dirty word. Andrew Old shatters this misconception in these blog posts here and here; others teachers make this point in articles here and here. No new teacher should ever be blamed for disruptive behaviour in their classroom. Instead, they must feel they can lean heavily on strong behaviour systems in their first term and year, and have help from senior leaders. Consistent consequences, routinely enforced and constantly reinforced by the Senior Leadership Team, are the best way to prevent misbehaviour.

Schools succeed when they enforce consequences consistently

There are some brilliant schools in tough areas who get this right. For example, one London school five or so years ago was faced with an epidemic of disruptive behaviour that was preventing pupils from learning in class. The solution was consistently enforcing a clear behaviour management policy, across all departments and years, with senior leadership highly visible by pupils and accountable to the headteacher for enforcement. New staff induction now routinely trains all new teachers in whole-school consistency on behaviour, and managers encourage them to lean heavily on the system. The watchwords of senior managers are to be ‘consistent, insistent and persistent’. Today, the school has narrowed the gap in GCSE attainment between pupils on FSM and those not on FSM from 28% nationally to 1%. It has established an ethos that eliminates low-level disruption. Pupils know that it is customary to behave in lessons and all senior managers hold themselves and one another accountable for enforcing consistency. Academic results have soared in the new era of consistent enforcement. If it can happen in inner-city London, there’s no reason it can’t happen all over England.

We must enforce rigorous national accountability

How can we ensure this happens nationally? Disruptive behaviour in English schools is a national problem; systemic problems require solutions at a national system level. While some schools have achieved great consistency in behaviour management, other schools still have not. National accountability must now ensure that all senior managers take responsibility for eliminating the disruption that stops pupils achieving their aspirations. Here’s what headteachers and policymakers can do about it:

Headteachers should rigorously ensure all senior managers are accountable for whole-school consistency on disruptive behaviour. For instance, headteachers could hold monthly behaviour forums between new and supply teachers and senior managers to check that support for enforcing behaviour consistently is happening. They could also provide staff induction that rigorously trains new teachers in how to consistently enforce the behaviour management system. Headteachers should ensure that there is a simple system in place for senior managers to support teachers who need to remove students from lessons, and that these teachers, especially early in their careers, are encouraged by all senior leaders to eliminate low-level disruption from their lessons, rather than blamed for not teaching well enough.

Policy makers should devise a clear, simple set of national guidelines for Senior Leadership Teams to achieve consistency on behaviour management, similar to Charlie Taylor’s checklists for teachers and heads. These guidelines could include suggestions that all senior managers are a visible presence at the school gate, corridors and in the lunch hall, enforce a whole-school system of deterrent sanctions outside of lessons for offences such as fighting, and routinely follow up every detention missed by any pupil. These guidelines should be Ofsted’s first port of call on inspections.

As John Donne recognised four centuries ago, senior leaders need to realise the bell tolls not for others, but for them.

See Policy First’s full report, with the behaviour problem on p15, and solution on p35.

Since I wrote this, TES behaviour expert Tom Bennet has posted a brilliantly simple, clear prescription for how we solve the behaviour crisis.

Not that I disagree in principle FOR ONE MOMENT, but…

There is a certain irony that “[enforcing] rigorous national accountability” was actually one of the drivers that put us where we are:

(1) We need to enforce behavior standards.

(2) We need to measure behavior in order to enforce it.

(3) We can’t do that (easily) but when kids behave badly they are excluded, so…

(4) We can use exclusions as a proxy for behavior – if there are fewer exclusions, the kids must be behaving better… right?

(5) We start judging schools on the number of exclusions.

(6) Schools start “teaching to the test” – i.e. in this case NOT excluding; because they get “punished” for doing so.

(7) These schools have no remaining sanction whatsoever for poor behavior.

(8) Let the vicious cycle begin…

Reblogged this on Scenes From The Battleground and commented:

I can’t resist reblogging this post from Joe Kirby, not just because it mentions me a lot, but because this is the agenda I had when I first started this blog.

One thing I’d disagree with: Not only NEW teachers shouldn’t be blamed for pupil misbehavious; NO TEACHER SHOULD BE BLAMED FOR PUPIL MISBEHAVIOUS. The person misbehaving is the only one to blame.

misbehaviour

It would be very helpful if you, and others that you mention such as Charlie Taylor, would name the schools that you think are performing well. Partly this is, or should be, a basic principle of argument: put your readers in a position to disagree with you. Partly because there is always more about a good school than can be put in a blog post, and readers will often want to take a deeper look. Partly because, and consistent with your argument, praising good behaviour publicly is important.

So which school is it?

Thoroughly articulates what myself and other colleagues say. I find it very difficult not to take bad behaviour in my classes personally. Equally I find it just as hard to change a whole school system that doesn’t provide consistency for staff. Thank you for articulating this in a way I can use.

Any chance of getting larger / clearer versions of charts 1 and 2?

. Behaviour for Learning, to me, is that a student chooses to engage positively with the work, their peers and their teachers to strive for learning. Thus they make the choice to learn.

Too often, and I’m afraid as outlined in the posts above, our behaviour management strategies focus on achieving good BEHAVIOUR or COMPLIANCE. This should not be thought to mean “behaviour for learning” and I fear this is what a lot of people mis-judge.

What I feel a lot of “BfL” strategies achieve is merely nothing more than “compliance” – getting students to adhere to a set of rules is very different to a student choosing to adopt or adhere ot a set of behavioural standards which will promote learning The former does not promote a sense of worth or value or indeed altered perception as to the value of good behaviour. Instead, they behave because they are “rewarded” with an external stimuli (often not learning related) or worse they are taught to behave to avoid consequence. Anyone who has see the appauling rates of re-offending in this country will not need swaying that this approach does not work.

In short, our behaviour management culture in this country promotes an external locus of control and promotes the need to comply or die – this approach does no consider the need to develop students and does not help students to make good choices for themselves. indeed to help them to believe they can make changed for themselves.

Another problem with such an approach is that there is no attempt to actually understand what the cause of the behaviour is. As a psychologist, seeing how teachers sell or apply behaviour management strategies sometimes scare me and perplex me. To attempt to manage behaviour without understanding

a) the route cause

and b) without consideration to the true outcome of your strategy.

is bonkers. For example. , as you have said above, disruptive behaviour and low confidence as two key issues in schools….I say, could they perhaps be interlinked? To not consider such a possible link Is utterly bonkers. Any intervention outcome, without considering the cause (both individual, whole class or school culture) would be short term, misunderstood by pupils and avoid any long term sustainable change.

We don’t need to train teachers in behaviour management techniques – if this was the answer, we would have solved the problem by now. The real problem is that teachers are not equipped in the psychological knowledge and practices which can help them to understand why people behave the way they do – i.e. understanding the cause – what we need to do is show teachers how to engage in strategies to UNDERSTAND the causes of the behaviour on both an individual and wider group level (so idnividual psychology but also the dynamics of social psychology) in that specific classroom, and then to use their pedagogical knowledge to find how they can find the solution. This will go a long way in creating a culture for learning, rather than a culture of compliance.

Despite all this, I believe we need to turn the question on its head. I feel sometimes that we assume that great behaviour comes first, and only then can we achieve learning. Why cannot it be the other way? Maybe they have lost trust that they will learn and they need to shown it is possible!

I have a very effective behaviour management system. It works on 95% of children, young people and adults. Furthermore, it is completely backed by motivational research, cognitive psychology and social psychology.

Outstanding Teaching and Learning.

When anyone feels

1) Suitably challenged

2) Inspired and engaged – they see the value in what they are doing

3) that there is adequate support structures in place which can help – so they feel safe

4) A teacher who has invested time developing their students resilience and self efficacy – so they feel they can achieve the challenge

5) like they are making clear progress – so their feelings are supported by evidence

6) they know what to do (and feel they can) know where to go next.

5) and the others around them feel the same – so their is the social acceptance of making learning progress

The overwhelming majority of “bad behaviour” fades into the mist. Why would they want to misbehave when there is something engaging to do,m that they can learn from and they can work with? I say most of the time we need to show students first just how amazing learning can be, then we get choice and buy in into behaving.

As an experienced teacher/manager and, though I say so myself, a pretty good disciplinarian, I would say Neil G, though no doubt with the best of intentions, has outlined the perfect recipe for indiscipline and misconduct in schools.

It often isnt possible to immediately understand the complexities and motivations of the 30 souls in front of you. This is where ethos and clear rules come into play.

Some schools have fantastic behaviour yet some have appalling behaviour. Sometimes with the same school some teachers have ‘magical discipline”, some cannot keep the kids quiet for 10 seconds.

The successful schools and successful teachers are the ones who insist on standards, standards that are considered desirable in of themselves.

Yes, well taught and engaging lessons are essential but so are rules and cooperation, be it voluntary or ‘insisted upon’.

I wish to retain my anonymity so I cannot invite Neil to teach for 2 weeks in my school or my (more demanding) partnership school to put his marvellous system into practice. I feel it would provide invaluable enlightenment for him.

I have over the years met many teachers who voiced similar or identical opinions to Neil (far too many I am afraid) and I would describe their classrooms as chaotic, intimidating and sometimes even dangerous.

Respect and learning came a long way behind loudness, peer pressure and aggressive conduct in such environments.

ps Im aware that some ‘long termers’ in ‘ok’ schools can muddle along with a smile and a ‘matey’ approach with the kids. They rarely impose sanctions and get ‘some’ work out of their kids. But the acid test is how a new teacher comes to a school full of ideas and passion who gets insulted, assaulted or intimidated by kids every other lesson, no matter how good their talents and planning.

pps and we havent even touched upon the bullying issue which blights kids lives in many schools. For the sake of the victims we dont always have ‘time’ to work through the myriad of personal issues of the assailant- so the ‘zero tolerance’ policy must apply even if the assailant doesnt fully appreciate the reasons why bullying is unacceptable.

Pingback: Why isn’t our education system working? | Pragmatic Education

Having read your very good blog post, Joe, I was thinking that in my experience there are three main reasons for poor behaviour.

1. Emotional/ social chaos in a child’s life that over rides anything any teacher might do or say to reach out to them.

2. Covering up feelings of failure/ low self esteem because a child cannot “get” the work, and they see others succeeding and bad behaviour is a way out to keep their self respect. This is closely linked with misbehaving to get attention and/or friends, again due to low self esteem.

3. A child genuinely feeling that what the teacher is teaching is “pointless” or “boring”, or they know it all already. I will confess that I myself misbehaved for this reason in many lessons and apologies to my Latin and History teachers when I was 15/16…

School systems do not always address these as separate issues, or have proper measures in place to deal each with them effectively.

When I read Neil G’s comment it therefore made complete sense, especially for the category 3 students, with just one proviso- there are students that even the most outstanding of teachers cannot reach. And in some schools they are there in large numbers. Hence the need for SLT to address behaviour at the highest level, and provide the social care and structure at school to support category 1 mis-behaving students so they start to engage with those outstanding teachers. Category 2 demands a sophisticated approach to SEN, and immense amounts of staff training so we can all differentiate properly.

Pingback: How can we improve Initial Teacher Training? | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: A guide to this blog | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: How can we improve our education system? | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: How can we improve our education system?

Pingback: How can we create great school ethos? | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: How can we create a vibrant staff culture? | Pragmatic Education

Joe – just revisiting this several months on. Have enjoyed watching the first two episodes of ‘Educating Yorkshire’ and it’s causing me to reflect on disciplinary incidents I’ve had to deal with at different stages of my career. Exactly thirty years ago I started in a new role in my first school as an Assistant Head of House (a school with a House-based pastoral system), and had my first experience of dealing with incidents that hadn’t happened in my own classroom, and I continued to deal with discipline in subsequent roles as Head of Department, Head of Sixth Form, Deputy Head and Head. I certainly didn’t always get it right, and watching EY is encouraging me to think back and analyse what happened and why.

As I’ve said elsewhere, I was a deputy and then a head in two girls’ independent day schools, and I’m sure there are some who think that there wouldn’t be discipline issues in such schools. Of course there were – perhaps less of the ‘stamping on her head’ variety (last week’s EY) but plenty of low level poor behaviour and subtle bullying – which are arguably even harder to deal with.

Watching EY I’m struck by how much of Jonny Mitchell’s time is taken up with discipline – even given the programme editing process which may distort the picture, he admits himself that he gives a huge amount of time to this. It can be draining and can grind you down, but Senior Leaders and heads just can’t give up. Like parents with your own children, if you get tired of constantly reinforcing the rules and boundaries and start to let things slip, you’re done for! But it’s easy to say and can be difficult to do.

The other thing that occurred to me, watching EY last week, is the crucial issue of whether/how you get a pupil to take responsibility for their own choices and actions. Sometimes they will, and sometimes they really can’t seem to see beyond the ‘it was his/her fault and I’m being picked on’ mentality. It’s like any sort of self-awareness – you can’t easily help others to develop it but if someone isn’t self-aware it can be so hard to get through to them.

And finally, on the subject of responsibility, I fully accept that if pupils misbehave, it’s their fault/responsibility rather than the teacher’s, BUT it IS the teacher’s responsibility to deal with it – with support in the most difficult cases. And it’s also the teacher’s responsibility to ‘forgive’ and move on when it has been dealt with, and not to bear a grudge. Stephen Drew illustrated this brilliantly in ‘Educating Essex’.

Sorry for such a long post!

Pingback: A summary of ideas on this blog | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: What Sir Ken Got Wrong | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: Books, bloggers & metablogs: The Blogosphere in 2013 | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: Free Thinking: I agree with Katharine | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: A guide to this blog | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: What Sir Ken Got Wrong | Pragmatic Education | Magnitudes of dissonance

Pingback: Useful bits and pieces – A Chemical Orthodoxy

Pingback: Social Action: Proposal – Cecily Lane Bedner